Most Popular

Out of the Shadows

-

1

A defense attorney's perspective on Korea's real drug challenges

-

2

Body heat scanners help hunt for drugs at airport

-

3

Enemy within: Illegal drug cases rare but rising in barracks

-

4

Surviving drug addiction: Peers from Korea, Japan share their stories

-

5

Tell the truth: Advanced drug education needed to curb teen exposure, experts say

[Out of the Shadows] Tell the truth: Advanced drug education needed to curb teen exposure, experts say

Adolescents’ drug problems reach point where educational videos no longer sufficient

By Park Jun-heePublished : Oct. 2, 2023 - 16:01

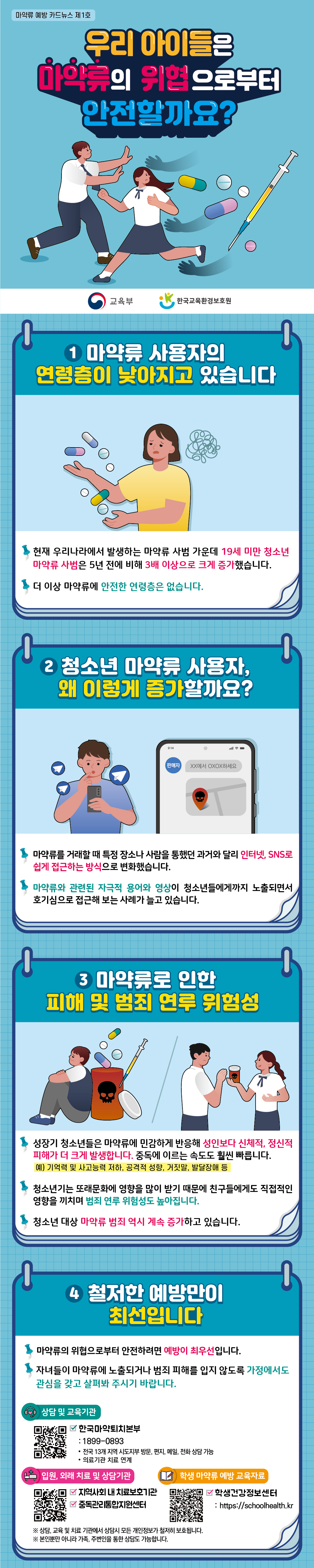

Drug prevention education has long been thought of as a criminal issue in South Korea, but an increase in teenage drug offenders has led to wider calls for enhanced drug education.

As concerns grow over adolescents’ shallow awareness of drugs due to a lack of education, politicians on both sides of the aisle are also demanding more thorough drug abuse prevention.

In November last year, Rep. Lee Tae-kyu of the ruling People Power Party proposed a bill that would make drug prevention programs a mandatory part of the curriculum in schools nationwide, stressing that adequate education is crucial to preventing children’s exposure to drugs.

In the same period, Rep. Seo Dong-yong from the main opposition Democratic Party of Korea also urged educating teenagers about the dangers of drugs, pointing to the lack of warning and education for the soaring number of young drug offenders.

But little has changed so far. Students in Korea still receive drug prevention education through videos, usually less than an hour long, designed to create awareness and encourage students to “just say no” to drugs. Parents worry that a fact-oriented drug education program could make their children more likely to experiment.

This is a stark contrast to the curriculum in most Western countries, which covers content on how illegal substances are taken, how to recognize the signs of an overdose and what to do if encountering such a situation.

The Korean program also does not teach students about the role of drugs as medicine and their effects on the human body, and it does not contain adequate information on how to avoid medication errors.

The program also does not tell students about some drug controls. For example, the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety prohibits the prescription of the opiate fentanyl for noncancerous patients under the age of 18, but this information is missing from the curriculum.

Yet, illegally obtained prescription drugs are most popular among youngsters, and tabs of phentermine, or Dietamin, and fentanyl transdermal patches are the easiest to get due to loopholes in related regulations.

Attention has turned to whether changes in drug education can halt the trend, but a senior official at the ministry overseeing students’ health policy told The Korea Herald that it has no plans to make a drug education program part of the school curriculum.

Instead, the official said the ministry would engage more with the Korean Association Against Drug Abuse -- an organization under the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety that aims to prevent illegal drug use and drug abuse -- by offering drug abuse education taught by a visiting teacher from the group about the dangers of drug abuse through one-off presentations.

Also, the Education Ministry said it had distributed guidelines from police to each provincial office of education to help raise awareness on drug addiction and abuse in light of the Gangnam student drugging incident in April where students were given drug-laced drinks. The guidelines go over how students should respond to a stranger approaching them and how to report to 112 -- the emergency number for police -- if they experience a similar case.

After the incident, the South Korean government also mandated a minimum of 10 hours of drug prevention education in elementary to high schools in April this year. Under the scheme, students are educated on how their future will look 10 years after taking drugs to shape their awareness and promote a drug-free lifestyle.

Evidence-based drug education

But experts say adolescents need more comprehensive education on the harmful nature of drugs and the dangers of overdosing to stave off first-time usage of drugs and diminish curiosity. They say thorough evidence-based drug prevention education that students can digest is necessary, explaining that students need adequate resources and information to make health decisions in the future.

If the ministry is not planning to introduce a drug education curriculum, Yoon Heung-hee, a professor at Hansung University’s drug and alcohol addiction department, advises adopting the D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) program developed in the US, in which local police officers regularly come to classrooms to deliver an evidence-based curriculum on high-risk circumstances involving drugs.

Created in 1983, the D.A.R.E. program is a school-based substance abuse, gang and violence prevention program. In 2009, the program was revised due to criticisms of its ineffectiveness.

As of 2016, it has been adopted by 75 percent of US school districts and in 52 countries. More than 70,000 US police officers have taught the program to over 200 million students there.

A United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration report showed that students who received such anti-drug education had lower usage rates of marijuana and tobacco.

The Ministry of Justice plans to provide 1,300 drug education sessions to elementary and high schools nationwide this year, but the lectures are storytelling-based education to demonstrate to young people why they should not do drugs.

Yoon, who is also a former police officer who worked in narcotics for over 30 years, also recommends that the ministry team up with police to provide students opportunities to learn how drug offenders and smugglers are caught.

“Online-based educational videos (used in schools) don’t quite move the needle in raising awareness. Since it’s not fear-mongering, it triggers interest because it only tells students to ‘just say no to drugs’ without explaining why. The phrase is catchy, but the message doesn’t stick in students’ minds,” Yoon told The Korea Herald.

“The anti-drug message that says ‘drugs are bad’ only sets young people up for greater harm as they enter adulthood,” he said.

Yoon also noted that media education is needed for young people, citing the increased online drug trade.

“We should teach (students) about online safety and using social media safely so that they can make responsible choices and avoid bad situations,” Yoon said.

According to data the Korea Communications Standards Commission submitted to Rep. Park Sung-joong of the People Power Party on Monday, drug information was most commonly found on Twitter, now known as X, with a total of 14,779 cases last year, followed by other social media platforms like Tumblr, Facebook and Google.

Jeon Kyoung-soo, head of the Drug Criminology Institute of Korea, echoed Yoon’s view that schools need education programs that allow students to navigate the broad landscape of drugs and develop critical understanding.

Jeon said the government and the Education Ministry should take responsibility for safeguarding their young citizens from illegal substances.

“The government should be more honest about the harsh realities of drugs and how they can ruin people’s lives. Because of its conservative posture, many parents don’t want their children to know about drugs now and don’t even talk about drugs. Then how will students protect themselves when exposed to risky situations?” he said.

“Education begins by informing students about the facts and real-life scenarios they see about drugs. Evidence-based prevention will gradually stoke awareness.”

The Korea Herald is running a series of feature stories and interviews on the evolution and rise of drug crimes, insufficient support systems and young addicts’ stories in South Korea. This is the seventh installment. -- Ed.

![[Today’s K-pop] Treasure to publish magazine for debut anniversary](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/07/26/20240726050551_0.jpg&u=)