Most Popular

Korean History

-

1

2014 ferry disaster left scars that never healed

-

2

In 2012, K-pop makes leap from 'Gangnam' to the world

-

3

Deadly sinking of Navy ship in 2010 marks worst postwar military disaster

-

4

In 2008, Korea's National Treasure No. 1 went down in flames

-

5

In 2005, science world’s biggest scandal unravels in Seoul

[Korean History] Is reunification of Korea still a goal, 70 years on?

Data suggests once-ironclad resolve to unite Korean Peninsula may be waning among young South Koreans

By Yoon Min-sikPublished : Jan. 11, 2023 - 17:32

“History through The Korea Herald” revisits significant events and issues over the seven decades through articles, photos and editorial pieces published in the Herald and retell them from a contemporary perspective. – Ed.

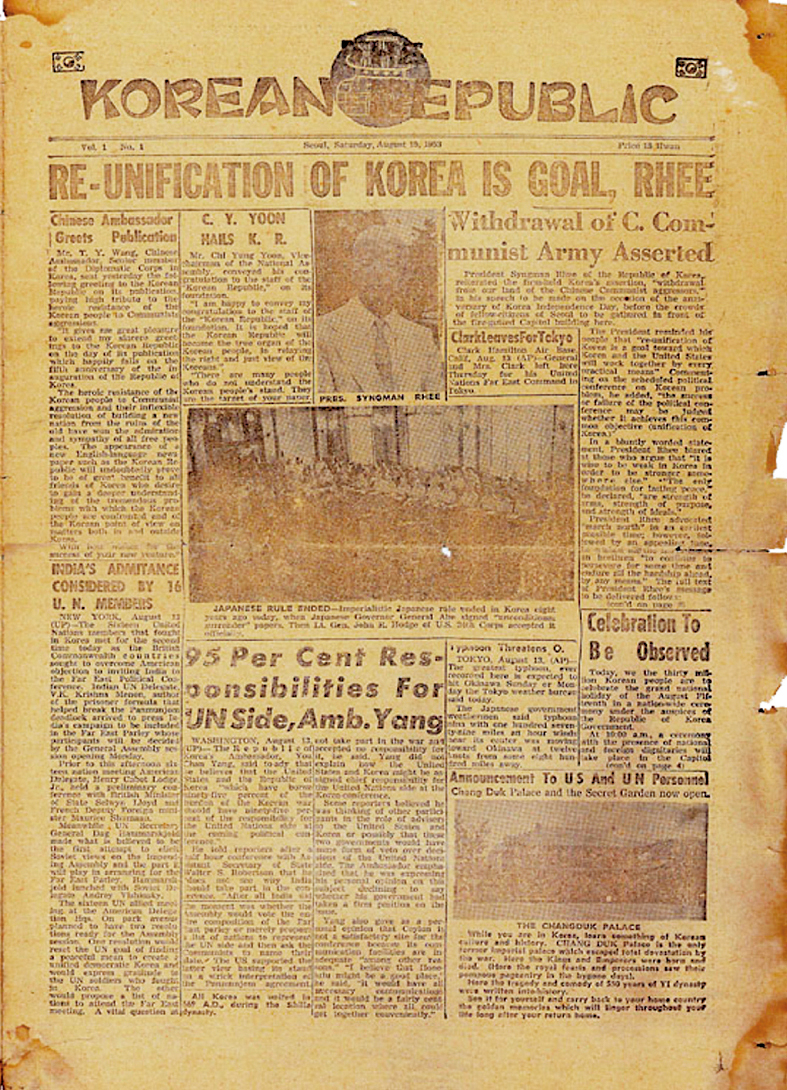

“Re-unification of Korea is goal, Rhee,” says the front page of The Korea Herald, then called The Korean Republic, in its founding edition on Aug. 15, 1953.

To today’s Koreans, this message from the late inaugural President Syngman Rhee may sound like hollow rhetoric. But to those who lived through the forced division of Korea between South and North and the horrors of a war initiated by the communist forces of the North, it must have felt very different.

When Rhee said “unification,” he meant the recovery of the Northern territory by military force if necessary, according to a declassified US diplomatic document.

Fast forward to 2023, and unification remains a national goal. There is even a government ministry dedicated to it, fittingly named the Ministry of Unification.

However, compared to 70 years ago there is a wide gulf between political leaders’ and the public’s perceptions on the need for unification, and how to achieve it.

Is unification necessary? Answers changed over time

The question, although it may sound simple, brings with it a series of hard questions. Should the two different political systems of North and South Korea be allowed to remain in a loose form of union, or should the South absorb the North into its free democratic system? If so, who should bear the costs? Do people want this to happen in their own generation, or at a future time?

In the post-Korean War days up until the 1960s, animosity toward the communist invaders persisted, affecting all talk of unification.

Such belligerence is shown through nationwide rallies for unification that took place in 1954, during which the people marched in major cities across the country holding picket signs saying, “Unification through Northward Advance.”

In the aforementioned US declassified document dated Oct. 25, 1959, then-US Under Secretary of State Clarence Douglas Dillon reported to US President Dwight D. Eisenhower that South Korean leader Rhee “emphasized Korean impatience with lack of progress toward unification” and “expressed conviction only way to unify Koreas was by military force.”

According to Professor Kim Jin-hwan of the National Institute for Unification Education, who published a study in 2015 about changes in public perception toward unification, the first public survey on the issue occurred in 1960. It asked around 2,400 South Koreans to choose their preferred method of uniting the two Koreas. Over 61 percent said they were “unsure,” while 19 percent chose “a general election of Koreas under surveillance of the United Nations.”

The first survey asking whether the Koreas should be reunified at all was conducted in 1969 by the Board of National Unification -- a forerunner for the Unification Ministry. It showed that 90 percent of the 2,014 respondents said unification was necessary, with 38.5 percent saying it was possible within the next 10 years.

By the 1980s, public opinion polling had become more common and surveys conducted during this time showed fluctuations in South Koreans’ perceptions, largely affected by hostile events in bilateral relations.

In 1983, the North attempted a terrorist attack on then-South Korean President Chun Doo-hwan in Myanmar, then known as Burma. A jointly conducted survey by local DongA Ilbo and Asahi Shimbun of Japan the year after showed that 48 percent of South Korean respondents saw unification as “impossible.”

A change in mood came in late 1980s when the capitalist and communist blocs showed signs of reconciliation. This reached a pinnacle with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the Soviet Union in early 1990s. The 1988 version of the aforementioned DongA-Asahi survey reflected this change, with the percentage of those who “hate North Korea” dropping from 76.5 percent in 1984 to 59.4 percent. Those who thought unification was impossible, however, was 43.6 percent, only a slight dip from four years before.

The 1998 election of then-President Kim Dae-jung -- the first leader in the country’s history from the liberal faction -- sparked expectations for improved relations with the North.

A survey, conducted the following year by the state-run Korea Institute for National Unification, showed that while 82.58 percent of respondents agreed to the need for unification, South Korea needed to wait for the right time.

Some 6.25 percent in the 1999 KINU survey were in favor of immediate unification, a drop from 19.3 percent in 1998, while those preferring the Koreas to remained divided also dropped to 7.5 percent.

In 2005, with two consecutive liberal leaders who emphasized improving inter-Korean relations taking the helm in South Korea, 49.2 percent said they wholeheartedly agree to the notion that “unification of the Koreas is the nation’s task that must be accomplished” while another 34.7 percent somewhat agreed.

In more recent years, South Koreans’ urge to unify with the North has waned. More prefer the peaceful coexistence of the two Koreas, according to multiple studies and surveys.

A 2021 report by the KINU shows that the national preference for unification had dropped every year from 37.3 percent in 2016 to 22.3 percent in 2020 -- before rebounding slightly in April of 2021 to 25.4 percent. But the preference for peaceful coexistence of the two Koreas has increased every year in that period, from 43.1 percent in 2016 to 56.5 percent in 2021.

The report also showed that the preference for separate Koreas was particularly high among younger Koreans.

The preference for the separate, peaceful coexistence of South and North among those born after 1991 was 71.4 percent as of 2021, the highest among all age groups. Only 12.4 percent from this group wanted unification, the lowest figure out of any age group.

The group of those born between 1981 to 1990 was also the second-highest in not wanting unification, with 55.9 percent preferring coexistence.

“The trend among the young generation of wanting coexistence with North Korea instead of unification is expected to become stronger in the future,” the researchers wrote.

With this year being the 70th anniversary of the end of Korean War, the data suggests that more Koreans have become accustomed to the existence of a communist state occupying the northern part of the peninsula.

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Today’s K-pop] Ateez confirms US tour details](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050700_0.jpg&u=)