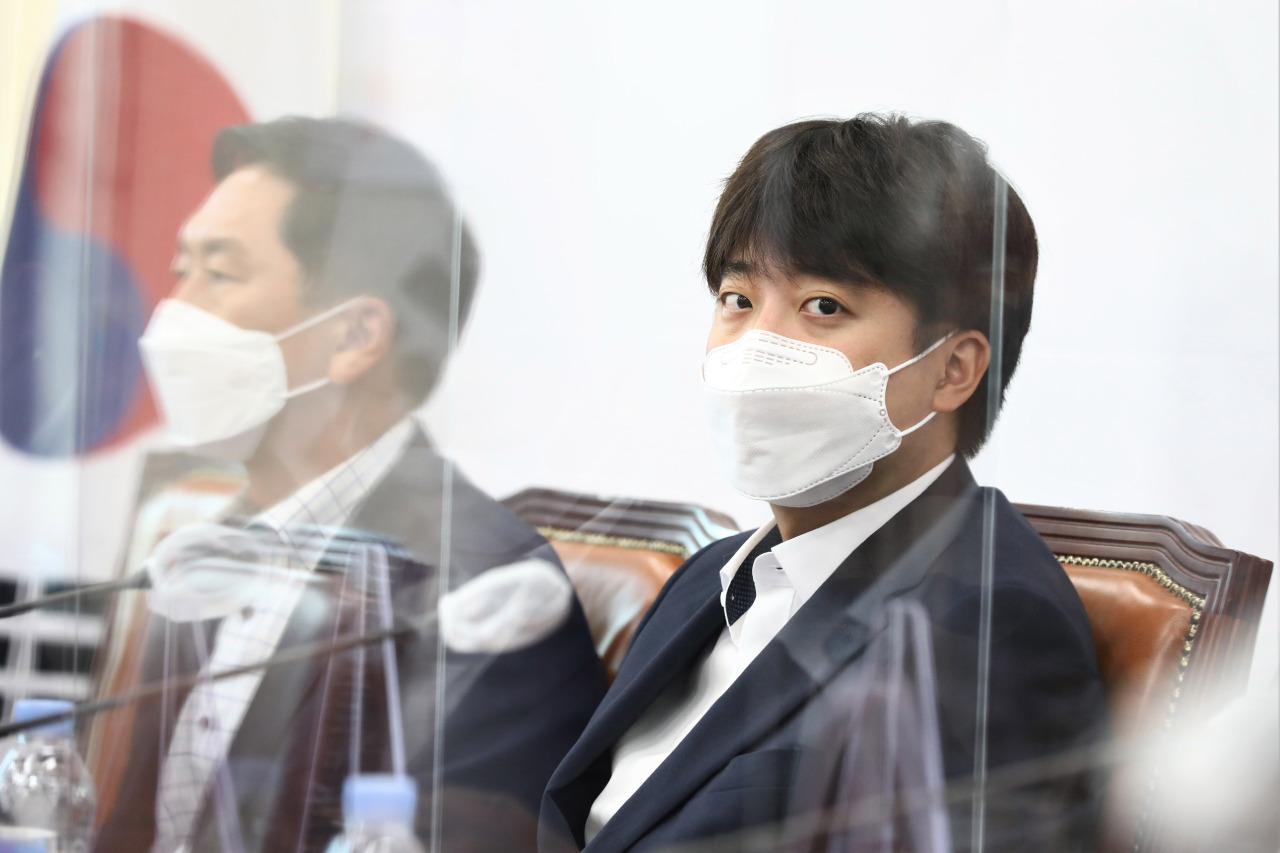

[Us and Them] Lee Jun-seok and the rise of anti-feminism

How the conservative party’s young boss became a hero for internet misogynists

By Kim ArinPublished : Sept. 6, 2021 - 18:12

At 36, Lee Jun-seok made history by becoming the youngest-ever leader of the main opposition People Power Party. His success has fanned hopes for significant changes in the political arena, but an uglier side of South Korean society has ascended along with him.

Two months before he was elected party chairman, the party won the Seoul and Busan mayoral by-elections. Although the candidates were favored across age groups, young male voters showed overwhelming support.

Post-election analyses say the results reflected the current administration’s failure to address the bleak realities facing young Koreans, but Lee put a twist on that.

Lee said in a Facebook statement that the Democratic Party had lost the elections because of its “fixation on a pro-women agenda” and that the ruling party had “underestimated the participation of men in their 20s and 30s.”

In an April media interview, Lee attributed the overwhelming support his party received from young male voters to their anger toward feminism, saying, “Ask any 20-something man and he’ll say it’s feminism.”

“Lee made it about young men and their anti-feminism,” Shin Jin-wook, a sociology professor at Chung-Ang University, told The Korea Herald.

“He catered to the untapped pool of angry young men who felt they lacked representation in politics, and made feminism -- rather than the failure of our leaders -- the scapegoat of their problems.”

Lee’s comments appear to have built something of a fandom among online fringe groups marked by strong opposition to feminism.

One of them is FM Korea, one of the forums that was behind the cyberbullying of 20-year-old Olympic archer An San based on the idea that she “looks like” a feminist.

“Lee Jun-seok is the only politician with the guts to stand up against feminism, when femis (feminists) are at the top of the power hierarchy in Korea. That’s why we have to support him,” one poster wrote on the forum.

Another such group is New Men on Solidarity, whose slogan is “feminism is a mental illness.” The group’s president told a media outlet in June that he found Lee’s election as party leader to be “empowering” and “very significant in that it showed men can join forces, and be heard.”

“Although the cyber misogyny is nothing new, Lee came along and gave them a voice. Lee’s rise has emboldened them,” Shin of Chung-Ang University said.

“Once a politician like Lee picks it up and speaks their language, it becomes a part of the mainstream discourse, assumes legitimacy and ceases being ‘just an online phenomenon.’”

For his part, Lee denied he had belittled women, saying he simply believed in equality of opportunity rather than “equality of outcome enforced by gender quotas,” at a public meeting in April.

In a June interview with a local newspaper he elaborated, saying he was challenging “radical feminists,” not “regular women.”

Regardless of intent, Lee has played up and advocated a host of “skewed notions and a false sense of victimhood” says political sociology professor Kim Yun-tae of Korea University.

Lee’s calls for axing affirmative action in the name of meritocracy, for one, echoed a misconception harbored by the online cohort of men that women have the advantage in Korea’s workforce.

Lee has said affirmative action programs promote “reverse discrimination” against men and that the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family should be abolished. Women today do not face discrimination and are no longer deprived of any opportunities or privileges, he has said.

As Kim pointed out, global indexes indicate otherwise. In 2020, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development reported Korea had the widest gender pay gap among the members it surveyed, and the World Economic Forum placed Korea 102nd out of 156 countries in terms of the gender gap.

Government statistics show that men are increasingly the beneficiaries of legislation meant to guarantee equal employment rights in the public sector. In the 17 years since the law has been in place, almost twice as many men as women have been hired after not making the initial cut.

“The term meritocracy was originally coined as a dystopian satire -- it has nothing to do with fair competition,” Kim said. The kind of “neutral” approach proposed by Lee overlooks the disadvantages women and minorities experience, he said, and serves to justify the status quo by portraying discrepancies as deserved.

“If Lee is truly oblivious to, or can afford to look past the systemic sexism in Korean society because it doesn’t affect him, that in itself is a privilege.”

While Lee’s approach may have met with some success, many say it cannot last long and could prove to be a liability for the conservative opposition.

“It’s hate-driven populism, which works to fan and justify animosities toward minorities,” Shin Kyung-ah, a sociology professor at Hallym University specializing in women’s studies, said.

Political commentator Rhee Jong-hoon said, “Lee likes to fashion himself as the voice of younger generations in politics, and a part of his initial popularity was owed to expectations that he, by virtue of being young, would be different from established politicians.”

He said if Lee truly cared about young Koreans, there was a plethora of issues he needed to tackle, such as joblessness, housing and suicide.

Lee’s divisive words, which have won over some, are not an asset but a liability in the long term, Rhee said.

“It can’t last long,” Rhee said. “As a leader he should strive to heal the country and bring people together instead of aggravating the divide.”

By Kim Arin (arin@heraldcorp.com)

The concept of “us” is a strong force in Korean culture, and to be counted as “one of us” in any group comes with privileges big and small within its boundaries. However, for those who fall outside the boundaries of “normal,” life in Korea can be riddled with hurdles and sometimes open hatred. In a series of articles, we take a closer look at the biases that exist in Korea, and the lives of those branded as “them” by mainstream society. -- Ed.

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)