Protests over tuition cuts signal partisan race to woo voters with populist policies

Opposition leader Sohn Hak-kyu hoped that his party’s plan to cut college tuition fees would appeal to students when he attended their rally early last week.

“I am not here to add fuel to your anger but to share your concerns,” Sohn told about 200 university students holding a candlelight vigil in downtown Seoul for a ninth straight day.

Opposition leader Sohn Hak-kyu hoped that his party’s plan to cut college tuition fees would appeal to students when he attended their rally early last week.

“I am not here to add fuel to your anger but to share your concerns,” Sohn told about 200 university students holding a candlelight vigil in downtown Seoul for a ninth straight day.

But as soon as he started explaining his party’s efforts to reduce school fees, students reacted angrily.

“What’s the difference with the (ruling) Grand National Party?” a student asked. Other students pressed Sohn, chairman of the Democratic Party, to immediately work out measures to halve tuition fees.

At a meeting with party lawmakers the following day, Sohn pledged to draw up a scheme to halve tuition fees at all universities from the following spring semester. He came under fire for jettisoning overnight his party’s policy of giving half-tuition benefits to students from the poorest 50 percent of households.

But a party spokesman defended Sohn’s move, saying that there was nothing wrong with adjusting policies on the spot. Rep. Chung Dong-young, a member of the party’s Supreme Council, went further to suggest the DP should consider repealing tuitions if it took power in next year’s presidential election.

With the more generous scheme, Sohn joined a massive candlelit vigil last Friday, which drew more than 5,000 students and civic group members. “Today marks a victory of democracy for people’s livelihood,” declared Sohn, flanked by his counterparts from three other smaller opposition parties.

The ruling GNP was in no position to denounce the DP leader for riding the wave of student anger and frustration at the tuition fees that have been weighing on many households. Recent remarks by new GNP floor leader Hwang Woo-yea had prompted students to take to streets to call for tuition cuts.

Hwang told a meeting with reporters on May 22 that he would seek ways of reducing college tuition fees “at least in half,” rekindling debates on the issue. He later took a step backward, saying what he had meant was to significantly relieve students and their families of the tuition burden.

The ensuing discussion between ruling party and government officials was stalled over how to raise the necessary funds, estimated to exceed 3 trillion won ($2.76 billion). A week later, hundreds of college students gathered at a plaza in downtown Seoul to demonstrate for a 50 percent reduction in tuition, which was also one of President Lee Myung-bak’s campaign pledges.

Political calculations

While agreeing on the need to reduce tuition fees, critics denounce both the ruling and main opposition parties for approaching the educational issue with a view to expanding voter support in next year’s parliamentary and presidential elections.

They express concerns that the competition between the rival parties to woo votes with populist pledges will spiral out of control.

“The political circles seem so preoccupied with winning votes as to lack visions for the nation’s higher education,” said Jaung Hoon, political science professor at Chung-Ang University.

Kim Hyung-joon, politics professor at Myongji University, said that the two major parties had discarded their responsibility by igniting the tuition issue without having prepared measures to deal with it.

“We are now in a situation where politics is not just regressing but totally abandoned,” he said.

Critics say the parties should have made a comprehensive and thorough review of how to resolve the issue including the restructuring of colleges that have sprung up since the 1990s before rushing to curry favor with students.

Some note that political circles are to partly blame for the current problems by allowing too many new colleges and college entrants. Government figures show more than 3.6 million students now attend 411 universities and colleges across the country, with about 80 percent of high school graduates entering higher institutes of education, compared to an average of 30 percent for European members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Political observers also indicate that politicians had until recently paid little attention to the problems of students and their parents, even though protests against tuition hikes became a common scene at campuses long ago.

“Where were all the politicians when we repeated our demand for tuition cuts at the start of every semester over the past years?” said a 23-year-old senior surnamed Kim at a Seoul university. “Even when there were reports of some students committing suicide after being driven into the corner by economic hardship, our voices failed to reach politicians’ ears.”

According to figures from the Education Ministry, tuition fees rose by 82 percent over the past decade, while prices increased by 31 percent during the same period. From 2001 to 2010, tuition fees for private universities rose from 4.8 million won to 7.54 million won and those for public schools were up from 2.43 million won to 4.44 million won.

The ministry’s statistics showed tuition fees increased more steeply in the five-year rule of liberal President Roh Moo-hyun, which began in February 2003, than under the incumbent administration of Lee. The Roh government lifted the ceiling on tuition fees to help financially struggling colleges in provinces.

The GNP, then in opposition, first raised the idea of halving tuitions in 2006 as part of its manifesto for the local elections. Lawmakers of the then-ruling Uri Party, which was later reformed as the Democratic Party, criticized the GNP for trying to entice the public with populist measures that contradicted its stance of supporting a smaller government and tax breaks.

DP floor leader Kim Jin-pyo, who served as education minister at the time, also turned a deaf year to voices calling for reduced tuition fees, saying, “There is no longer the need to keep tuition fees low.” Kim is now at the forefront of his party’s drive to slash school fees in half.

Reckless competition

Many political commentators say the fuss over college tuition may signal more reckless competition between rival parties to win voters’ hearts by promising a wide range of welfare benefits regardless of their financial viability.

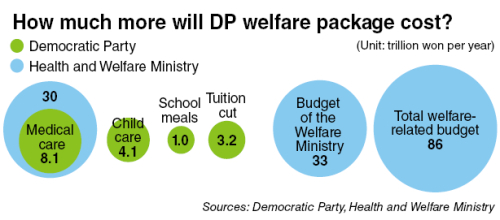

The DP had already put forward a set of free welfare measures early this year. The so-called three-plus-one package consists of free medical care, free child care and free school meals as well as tuition cuts. The party’s own estimates put the annual additional costs at 8.1 trillion won for medical care, 4.1 trillion won for child care, 1 trillion won for school meals and 3.2 trillion won for reduction in school fees. Health Ministry officials, however, forecast free medical care alone will require an additional fund of 30 trillion won per year.

On the back of its emphasis on improving people’s livelihood, the DP won an overwhelming victory in the April 27 by-elections. Buoyed by the election outcome, Sohn, who is emerging as the party’s strongest presidential hopeful, has pledged to continue focusing on easing economic difficulties facing working-class families.

Alarmed over its crushing election defeat, the GNP has not hesitated to shift from its conservative values to copy the DP’s welfare initiatives. It is reportedly pushing to expand financial support for the education of preschoolers to include children aged three to four on the heels of a recent government decision to fully cover preschool expenses for five-year-olds by 2016.

“Expanding child care support is the next policy goal following the reduction of college education costs,” a GNP official was quoted as saying.

Behind the GNP moves to increase welfare is a deepening sense of crisis that their lawmakers may be trounced in April’s parliamentary elections, clouding its prospects for the presidential poll in December 2012. In a survey of voters in May, support for the GNP remained slightly above 31 percent, compared to 34.5 percent for the DP. President Lee’s approval rating, which had hovered above 40 percent, plummeted to 27.3 percent.

Rep. Chung Doo-un, a two-term GNP lawmaker, argued that undecided voters would support the GNP only when the party walks the path of “centrist reform” to the point of the differences with the liberal opposition party being blurred.

Ringing alarm bells over the moves in the political circles, former Minister of Strategy and Finance Yoon Jeung-hyun asked ministry officials in his recent farewell speech to fight against the wave of welfare. “We should not be afraid of being isolated in our struggle against the spell of free benefits.”

Political observers are concerned that the populist competition between the rival parties will boil over especially in the presidential campaign late next year, as shown in the previous cases.

In past campaigns, presidential candidates pledged massive development and welfare projects that require huge amounts of money, and then faced public criticism when they failed to keep their promises.

After taking office, President Lee expressed regret at having made pledges during the 2007 campaign to move central administrative agencies to the Chungcheong region as planned by the Roh government and to build a new hub airport in the southeastern region. His attempts to reverse the pledges invited vehement protests from politicians and regional residents, with his revised plan on the Sejong City blocked by the parliament.

He has also failed to keep his other promises to keep the economy growing at an average annual rate of 7 percent and create 3 million new jobs. Lee’s two liberal predecessors had also been unsuccessful in implementing their campaign pledges. Like Lee, Roh had given voters assurances that the economy would grow by 7 percent annually and 2.5 million new jobs would be available during his presidency. Kim Dae-jung, who came to power in 1998, pledged to increase the per capita national income to $30,000.

Thorough scrutiny

A move has been brewing to keep political parties from going unchecked in putting forward campaign pledges that are financially unfeasible.

The National Election Commission is considering measures to make it obligatory for political parties and candidates to have their campaign pledges come under prior public scrutiny. According to an NEC internal review paper, obtained by a local daily, parties and candidates are obliged to present detailed plans for implementing their policies, including the schedule and funding, to the commission 60 days before the election.

A nine-member independent panel will be formed to scrutinize the plans and make public the results so that voters can take them into account when they go to polls. Under the measures, the commission will also require a president or other elected officials to submit an annual report on the progress in carrying out campaign pledges.

An NEC official said the commission has not yet officially undertaken the work to draft a revision to the election law but was ready to do so as soon as a related parliamentary committee makes a request.

By Kim Kyung-ho (khkim@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)