[Hwang’s China and the World] Everything roots in something, the reason Australia actively steps into the Indo-Pacific Strategy

By Choi He-sukPublished : July 13, 2022 - 15:23

Australia is a country that has multiple similarities with Korea. Both are considered middle powers, both are allies of the US and have China as the largest trading partner, and the foreign policies in both countries depend on the domestic governing power. Above all, looking back at our choices between the US and China, they were mostly based on “Anmi-kyeongjung,” depending on the security of the US and the economy of China. Just like Korea-China relations, Australia-China relations also have hit their lowest during the last few years. Australia’s relations with China began to become tense in 2018 when Australia ruled out the participation of Chinese telecommunications equipment company Huawei in the 5G network business in line with the request of the Donald Trump administration. In April 2020, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison called for a survey of the origin of COVID-19, targeting China, and the relationship became more frictional. In response, China imposed retaliatory high-rate tariffs on Australia. Unlike the former Prime Minister Morrison, who sided with the US, the relationship between the two countries has improved as Prime Minister Anthony Albanese took office.

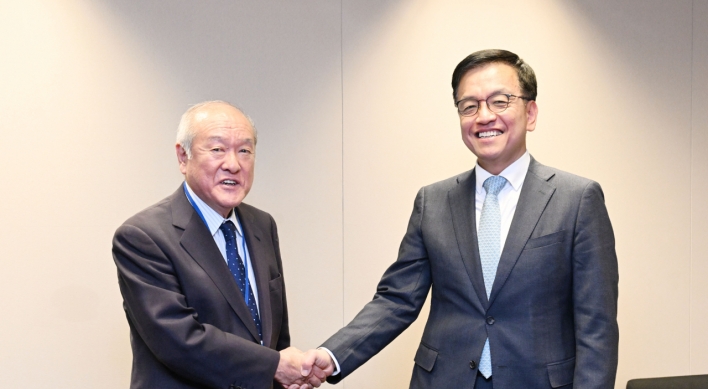

Australia has been actively involved in various US diplomatic, security, and economic initiatives, including the QUAD, Indo-Pacific Strategy, IPEF, NATO-AP4, and others. Will Australia alter its diplomatic, economic, and security stance? In this regard, this week’s interview invites professor Nick Bisley from Australia. He is the dean and head of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences and professor of international relations at La Trobe University, Australia. He has been a Senior Research Associate at the International Institute of Strategic Studies.

Hwang Jae-ho: Why did Australia rejoin the Quad again in 2018 after pulling out in 2007?

Nick Bisley: Australia was initially reluctant to join the Quad when it was first established in 2007. The country enjoyed very positive relations with all the region’s major powers and saw the initiative as risking positive ties with the PRC. A decade later and Australia perceives the region as much riskier and much more unstable. In particular, the government perceives that PRC’s ambition, its increased military capabilities, and the broader uncertainty in the regional security environment warrant the kind of focused minilateral group that the Quad represents.

Equally, its relationship with the PRC took a significant downturn in 2017 and, until the recent election of the Albanese government, was in its worst state since the establishment of diplomatic relations with the PRC in the 1970s. As such, the side costs of embracing the Quad were lower than before. A shifting strategic environment and the changes in its bilateral relationship with Beijing changed Australia’s perspective and have made it an enthusiastic member of the Quad grouping.

Hwang: Besides the China factor, what other reason is there for Australia to participate in The Quad?

Bisley: While Australia has the luxury of distance from acute flashpoints in the region, one of its core interests is stable regional security and, ideally, a favorable strategic balance in Asia. And it is this interest that is most directly challenged by the return of great power rivalry and Sino-American strategic competition. As a middle-ranking power, it has very limited ability to influence or shape the regional security setting. However, as a member of a multistate initiative, it can help advance its interests in the region. Australia’s enthusiastic embrace of the Quad also reflects a degree of skepticism of the existing multilateral security mechanisms, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum or other ASEAN-centered mechanisms, to do much to help stabilize the region. There is also an important bilateral dimension to Australia’s interest in the Quad: Australia’s relationship with India. Canberra has long wanted to improve its relations with India, both in security and economic terms. Yet over many decades, it has struggled to convert the desire for better ties into a substantively improved relationship with India. There are many reasons for this, relating to the history of colonialism, problems of capacity constraints in Canberra, and the fact that India matters more to Australia than the other way around. By regularly working with Indian counterparts through the Quad, Australia sees the opportunity to build a more robust foundation for relations with India through much more regular interaction on practical policy concerns.

Hwang: For Australia, China is the largest exporter and the largest importer. Considering this, why is Australia still in a confrontational stance toward China? How threatening does Australia perceive China to be?

Bisley: Since around 2016, Australian policy toward China has become dominated by security concerns. The efforts to balance economic interests with political and security concerns that had been the central focus of years past were set aside as perceptions of security risk outweighed all other matters. In part, these threats are related to the international environment, prompted by the PRC’s growing military power, its assertive behavior in the East and the South China Sea and its growing influence in the South Pacific. But the area that really accentuated the perception of the threat that Beijing posed was domestic. In particular, it was the belief that China was a malign influence in Australian domestic affairs. This included allegations that China was trying to influence domestic politics, concerns about Chinese intelligence activity in Australia, including allegations that Chinese intelligence operations were of industrial proportions made by the head domestic security agency and the belief that PRC economic activity within the country presented unacceptable risks. This led to the banning of Huawei and ZTE from participating in the country’s 5G telecommunication network development, the introduction of legislation intended to limit foreign influence in politics, and a number of investments from PRC-based firms being blocked by the Foreign Investment Review Board. These concerns, while real, were blown out of proportion and led to the deterioration of the bilateral relationship as well as significant problems for Australians of Chinese heritage who were the victims of overheated and careless rhetoric from the government and commentators denouncing the “Chinese” threat to Australia. This combination of domestic and international concerns has led Australia to have one of the most pessimistic assessments of the PRC in the region.

Hwang: How is the Ukraine war affecting Australian security?

Bisley: The Australian government has been one of Ukraine’s strongest and most vocal supporters, and its stance is bipartisan. The Russian invasion confirms the view in Canberra that world politics has entered a decisively more dangerous and unstable phase -- a mood it captured in its 2020 Strategic Policy Update that brought forward the timeline of strategic risk confronting the country. Canberra has committed to significantly increasing defense spending to prepare for this situation, and the Ukraine invasion reinforces the need to ensure this plan is sustained even in challenging economic circumstances.

Australia’s pessimism relates not just to a less stable balance of power but that the liberal system of rules and norms that have been so beneficial to the country over many years is at risk. The “no limits” relationship announced by Russia and the PRC before the February invasion reflects not just a security pact but an authoritarian challenge to liberal democracy, which has immediate implications for Asia. It will also make the efforts by the newly elected Labor government to try to improve relations with China more difficult, given the PRC’s support of Russia.

Hwang: How different are Australian parties’ China policies? How strong an influence does the domestic factor have on China policy?

Bisley: In its structural dimensions, Australian foreign and defense policy is firmly bipartisan. In the most recent election, the Labor Party, which won a narrow victory against the ruling conservative Liberal Coalition government, essentially presented the same foreign and defense policy as the government. The policy included reiterating support for the US alliance, commitment to the AUKUS arrangements to acquire nuclear submarines, and retaining strategic skepticism of the PRC. While bipartisanship is about policy in its larger orientation, the Labor party has a somewhat less hawkish approach to the PRC. It has argued and, since coming to power in late May, has indicated that it believes the country can have a productive diplomatic and economic relationship with China while retaining concerns about aspects of China’s policy. The Coalition government, since 2017, made clear that its security concerns would be the dominant factor shaping the bilateral relationship, even to the cost of the Australian economy. In contrast, the Labor party aims to have a more functional relationship and wants to put security concerns in proportion.

Hwang: Australia and Korea have strategic similarities. Australia and Korea are both allies of the US and have considerable economic exchanges and cooperation with China. Under these strategic similarities, Australia is more engaged in The Quad despite China’s warnings, while Korea is getting to step into US’s plan against China. How do you see Korea’s diplomacy?

Bisley: While there are some similarities between Australia and Korea, Seoul has had to navigate a more complex strategic setting than Australia. Korea is much closer to the PRC, and its economy is much more integrated with China’s than Australia’s. In Australia, we import consumer goods from the PRC and primarily export commodities; iron ore accounts for around two-thirds of Australia’s exports. FDI is not extensive and has been actively kept at bay by the government in recent years, so navigating the relationship with China is somewhat easier. Korea’s caution around the PRC makes sense, given its circumstances. That said, as a democracy that is closely allied to the US and which has a stake in a stable Asian strategic balance, it is probably in Korea’s interests to be looking at ways in which it can work, in coordination with others, to buttress the strategic balance and to help support liberal democratic values in a region in which authoritarian polities are growing in influence.

Up until now, Korea’s relative moderation in its foreign policy has been somewhat out of step with other liberal democracies, and a reconsideration of this approach would be welcomed by many countries both within Asia and beyond.

Hwang: President Yoon has announced a Korean version of the Indo-Pacific Strategy. What do you anticipate this Indo-Pacific Strategy to be?

Bisley: The Indo-Pacific has emerged recently as a way of describing two things. First, it is intended to describe a region that has thicker security and economic connections between the states and peoples of the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean Region. Second, it has been used by the US, its partners and allies to describe not just the geographic scope of the region but as an indirect way of describing a preferred manner in which the balance of power, as well as the rules, norms and values, operate in that region.

More specifically, it is about limiting China’s ability to change the regional balance or its rules and values. So any Korean Indo-Pacific strategy would need to reflect this larger theater of operation and grapple with the question of limiting China’s attempts to change the region. Given the complexity of Korea’s geoeconomic circumstances as well as the design of its military, any Indo-Pacific strategy is likely to be cautious in the first instance and focus most immediately on diplomatic and institutional dimensions rather than on military and security components.

For example, while it may not join the Quad at first, it may look at engaging with a number of the proposed areas of Quad cooperation that are focused on non-traditional security concerns, such as the Quad program on global health security or climate change. It may also include some areas of military interaction, but I would not expect those to be high profile in the first instance.

Hwang: How do you evaluate the feasibility of the IPEF?

Bisley: The IPEF is a very important, if belated, component of US strategy. Given how important the PRC economy is to the region and, more importantly, how effectively China has been using its economic influence to shape its relations with many countries, the US really had to have a much more coherent economic dimension to its Indo-Pacific strategy.

The problem that the US faces is that its greatest tool in this regard is something that, for domestic reasons, it is unable to use. Trade policy in general and improved access to the US market is of huge importance to countries. Yet circumstances in the United States mean that trade agreements are virtually impossible. So the US has to get creative to try to bind the economic interests of regional countries to those of its own.

The framework that it has put together is both impressive and underwhelming. It is impressive in that it has a large number of adherents, and it covers a wide range of areas of significance and for which multilateral cooperation is important. But it is underwhelming in the sense that we don’t really know how any of these mechanisms will actually work, and in this domain, precisely how the rules work and what exactly the incentives are matters entirely for how it will function. Also, given the diversity of economic interests in the region and the continued salience of the PRC, both its investment and markets, to many countries in the region, the US will find it difficult to advance its ends on this front significantly, at least under the current IPEF. There is a good chance that the framework will be a statement of good intent and not much more.

Hwang: Perhaps Korea’s early participation in The Quad is premature. Do you think Korea will be put in a position to join, regardless of whether Korea is willing to do so or not?

Bisley: It would be useful for the Quad and indeed the region to widen participation in its operations. A grouping with more members will increase its legitimacy, enhance its effect on the regional order and bring more capacity that can be used to shape the regional order. But expansion brings with it challenges, and these should not be rushed by a political imperative, particularly that of the existing members seeking to bring others into the fold. Any move by Korea to join the Quad or to engage in its activities should be determined entirely by Korea, particularly given the domestic challenges that participation might bring.

Hwang: How should diplomacy be between middle powers, such as Korea and Australia? Do you think middle powers have a certain level of autonomy and diplomatic space?

Bisley: Because Asia is a region in which a few very major powers’ interests clash, and because of the dominance of US-China rivalry in recent years, one can assume that only these great powers matter. Yet the recent past shows how middle-ranking powers have crucial roles to play, not only as the major power’s junior partners but as players in their own right. More importantly, times of great power rivalries increase the relative value of middle powers because of the way competition plays out and the benefits their action can bring to powerful states. And if middle-ranking powers work in coordination with others, either in institutional settings or in more ad hoc forms, they can play an outsized role.

To capitalize on these opportunities requires shrewd statecraft and a willingness to take on risks and costs which previously may have been avoided. The challenge is that, since the late 1970s, Asia has been strategically stable and one in which risky and costly statecraft was unnecessary due to this stability. Adjusting to this new environment, while it provides middle powers with influence, can be challenging, given that history. But both Korea and Australia have shown that in the past, they have the capacity to rise to the occasion, and I am confident that this will occur again.

Hwang Jae-ho is a professor of the Division of International Studies at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. He is also the director of the Institute for Global Strategy and Cooperation. This discussion was assisted by researcher Ko Sung-hwah and Shin Eui-chan.

Australia has been actively involved in various US diplomatic, security, and economic initiatives, including the QUAD, Indo-Pacific Strategy, IPEF, NATO-AP4, and others. Will Australia alter its diplomatic, economic, and security stance? In this regard, this week’s interview invites professor Nick Bisley from Australia. He is the dean and head of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences and professor of international relations at La Trobe University, Australia. He has been a Senior Research Associate at the International Institute of Strategic Studies.

Hwang Jae-ho: Why did Australia rejoin the Quad again in 2018 after pulling out in 2007?

Nick Bisley: Australia was initially reluctant to join the Quad when it was first established in 2007. The country enjoyed very positive relations with all the region’s major powers and saw the initiative as risking positive ties with the PRC. A decade later and Australia perceives the region as much riskier and much more unstable. In particular, the government perceives that PRC’s ambition, its increased military capabilities, and the broader uncertainty in the regional security environment warrant the kind of focused minilateral group that the Quad represents.

Equally, its relationship with the PRC took a significant downturn in 2017 and, until the recent election of the Albanese government, was in its worst state since the establishment of diplomatic relations with the PRC in the 1970s. As such, the side costs of embracing the Quad were lower than before. A shifting strategic environment and the changes in its bilateral relationship with Beijing changed Australia’s perspective and have made it an enthusiastic member of the Quad grouping.

Hwang: Besides the China factor, what other reason is there for Australia to participate in The Quad?

Bisley: While Australia has the luxury of distance from acute flashpoints in the region, one of its core interests is stable regional security and, ideally, a favorable strategic balance in Asia. And it is this interest that is most directly challenged by the return of great power rivalry and Sino-American strategic competition. As a middle-ranking power, it has very limited ability to influence or shape the regional security setting. However, as a member of a multistate initiative, it can help advance its interests in the region. Australia’s enthusiastic embrace of the Quad also reflects a degree of skepticism of the existing multilateral security mechanisms, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum or other ASEAN-centered mechanisms, to do much to help stabilize the region. There is also an important bilateral dimension to Australia’s interest in the Quad: Australia’s relationship with India. Canberra has long wanted to improve its relations with India, both in security and economic terms. Yet over many decades, it has struggled to convert the desire for better ties into a substantively improved relationship with India. There are many reasons for this, relating to the history of colonialism, problems of capacity constraints in Canberra, and the fact that India matters more to Australia than the other way around. By regularly working with Indian counterparts through the Quad, Australia sees the opportunity to build a more robust foundation for relations with India through much more regular interaction on practical policy concerns.

Hwang: For Australia, China is the largest exporter and the largest importer. Considering this, why is Australia still in a confrontational stance toward China? How threatening does Australia perceive China to be?

Bisley: Since around 2016, Australian policy toward China has become dominated by security concerns. The efforts to balance economic interests with political and security concerns that had been the central focus of years past were set aside as perceptions of security risk outweighed all other matters. In part, these threats are related to the international environment, prompted by the PRC’s growing military power, its assertive behavior in the East and the South China Sea and its growing influence in the South Pacific. But the area that really accentuated the perception of the threat that Beijing posed was domestic. In particular, it was the belief that China was a malign influence in Australian domestic affairs. This included allegations that China was trying to influence domestic politics, concerns about Chinese intelligence activity in Australia, including allegations that Chinese intelligence operations were of industrial proportions made by the head domestic security agency and the belief that PRC economic activity within the country presented unacceptable risks. This led to the banning of Huawei and ZTE from participating in the country’s 5G telecommunication network development, the introduction of legislation intended to limit foreign influence in politics, and a number of investments from PRC-based firms being blocked by the Foreign Investment Review Board. These concerns, while real, were blown out of proportion and led to the deterioration of the bilateral relationship as well as significant problems for Australians of Chinese heritage who were the victims of overheated and careless rhetoric from the government and commentators denouncing the “Chinese” threat to Australia. This combination of domestic and international concerns has led Australia to have one of the most pessimistic assessments of the PRC in the region.

Hwang: How is the Ukraine war affecting Australian security?

Bisley: The Australian government has been one of Ukraine’s strongest and most vocal supporters, and its stance is bipartisan. The Russian invasion confirms the view in Canberra that world politics has entered a decisively more dangerous and unstable phase -- a mood it captured in its 2020 Strategic Policy Update that brought forward the timeline of strategic risk confronting the country. Canberra has committed to significantly increasing defense spending to prepare for this situation, and the Ukraine invasion reinforces the need to ensure this plan is sustained even in challenging economic circumstances.

Australia’s pessimism relates not just to a less stable balance of power but that the liberal system of rules and norms that have been so beneficial to the country over many years is at risk. The “no limits” relationship announced by Russia and the PRC before the February invasion reflects not just a security pact but an authoritarian challenge to liberal democracy, which has immediate implications for Asia. It will also make the efforts by the newly elected Labor government to try to improve relations with China more difficult, given the PRC’s support of Russia.

Hwang: How different are Australian parties’ China policies? How strong an influence does the domestic factor have on China policy?

Bisley: In its structural dimensions, Australian foreign and defense policy is firmly bipartisan. In the most recent election, the Labor Party, which won a narrow victory against the ruling conservative Liberal Coalition government, essentially presented the same foreign and defense policy as the government. The policy included reiterating support for the US alliance, commitment to the AUKUS arrangements to acquire nuclear submarines, and retaining strategic skepticism of the PRC. While bipartisanship is about policy in its larger orientation, the Labor party has a somewhat less hawkish approach to the PRC. It has argued and, since coming to power in late May, has indicated that it believes the country can have a productive diplomatic and economic relationship with China while retaining concerns about aspects of China’s policy. The Coalition government, since 2017, made clear that its security concerns would be the dominant factor shaping the bilateral relationship, even to the cost of the Australian economy. In contrast, the Labor party aims to have a more functional relationship and wants to put security concerns in proportion.

Hwang: Australia and Korea have strategic similarities. Australia and Korea are both allies of the US and have considerable economic exchanges and cooperation with China. Under these strategic similarities, Australia is more engaged in The Quad despite China’s warnings, while Korea is getting to step into US’s plan against China. How do you see Korea’s diplomacy?

Bisley: While there are some similarities between Australia and Korea, Seoul has had to navigate a more complex strategic setting than Australia. Korea is much closer to the PRC, and its economy is much more integrated with China’s than Australia’s. In Australia, we import consumer goods from the PRC and primarily export commodities; iron ore accounts for around two-thirds of Australia’s exports. FDI is not extensive and has been actively kept at bay by the government in recent years, so navigating the relationship with China is somewhat easier. Korea’s caution around the PRC makes sense, given its circumstances. That said, as a democracy that is closely allied to the US and which has a stake in a stable Asian strategic balance, it is probably in Korea’s interests to be looking at ways in which it can work, in coordination with others, to buttress the strategic balance and to help support liberal democratic values in a region in which authoritarian polities are growing in influence.

Up until now, Korea’s relative moderation in its foreign policy has been somewhat out of step with other liberal democracies, and a reconsideration of this approach would be welcomed by many countries both within Asia and beyond.

Hwang: President Yoon has announced a Korean version of the Indo-Pacific Strategy. What do you anticipate this Indo-Pacific Strategy to be?

Bisley: The Indo-Pacific has emerged recently as a way of describing two things. First, it is intended to describe a region that has thicker security and economic connections between the states and peoples of the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean Region. Second, it has been used by the US, its partners and allies to describe not just the geographic scope of the region but as an indirect way of describing a preferred manner in which the balance of power, as well as the rules, norms and values, operate in that region.

More specifically, it is about limiting China’s ability to change the regional balance or its rules and values. So any Korean Indo-Pacific strategy would need to reflect this larger theater of operation and grapple with the question of limiting China’s attempts to change the region. Given the complexity of Korea’s geoeconomic circumstances as well as the design of its military, any Indo-Pacific strategy is likely to be cautious in the first instance and focus most immediately on diplomatic and institutional dimensions rather than on military and security components.

For example, while it may not join the Quad at first, it may look at engaging with a number of the proposed areas of Quad cooperation that are focused on non-traditional security concerns, such as the Quad program on global health security or climate change. It may also include some areas of military interaction, but I would not expect those to be high profile in the first instance.

Hwang: How do you evaluate the feasibility of the IPEF?

Bisley: The IPEF is a very important, if belated, component of US strategy. Given how important the PRC economy is to the region and, more importantly, how effectively China has been using its economic influence to shape its relations with many countries, the US really had to have a much more coherent economic dimension to its Indo-Pacific strategy.

The problem that the US faces is that its greatest tool in this regard is something that, for domestic reasons, it is unable to use. Trade policy in general and improved access to the US market is of huge importance to countries. Yet circumstances in the United States mean that trade agreements are virtually impossible. So the US has to get creative to try to bind the economic interests of regional countries to those of its own.

The framework that it has put together is both impressive and underwhelming. It is impressive in that it has a large number of adherents, and it covers a wide range of areas of significance and for which multilateral cooperation is important. But it is underwhelming in the sense that we don’t really know how any of these mechanisms will actually work, and in this domain, precisely how the rules work and what exactly the incentives are matters entirely for how it will function. Also, given the diversity of economic interests in the region and the continued salience of the PRC, both its investment and markets, to many countries in the region, the US will find it difficult to advance its ends on this front significantly, at least under the current IPEF. There is a good chance that the framework will be a statement of good intent and not much more.

Hwang: Perhaps Korea’s early participation in The Quad is premature. Do you think Korea will be put in a position to join, regardless of whether Korea is willing to do so or not?

Bisley: It would be useful for the Quad and indeed the region to widen participation in its operations. A grouping with more members will increase its legitimacy, enhance its effect on the regional order and bring more capacity that can be used to shape the regional order. But expansion brings with it challenges, and these should not be rushed by a political imperative, particularly that of the existing members seeking to bring others into the fold. Any move by Korea to join the Quad or to engage in its activities should be determined entirely by Korea, particularly given the domestic challenges that participation might bring.

Hwang: How should diplomacy be between middle powers, such as Korea and Australia? Do you think middle powers have a certain level of autonomy and diplomatic space?

Bisley: Because Asia is a region in which a few very major powers’ interests clash, and because of the dominance of US-China rivalry in recent years, one can assume that only these great powers matter. Yet the recent past shows how middle-ranking powers have crucial roles to play, not only as the major power’s junior partners but as players in their own right. More importantly, times of great power rivalries increase the relative value of middle powers because of the way competition plays out and the benefits their action can bring to powerful states. And if middle-ranking powers work in coordination with others, either in institutional settings or in more ad hoc forms, they can play an outsized role.

To capitalize on these opportunities requires shrewd statecraft and a willingness to take on risks and costs which previously may have been avoided. The challenge is that, since the late 1970s, Asia has been strategically stable and one in which risky and costly statecraft was unnecessary due to this stability. Adjusting to this new environment, while it provides middle powers with influence, can be challenging, given that history. But both Korea and Australia have shown that in the past, they have the capacity to rise to the occasion, and I am confident that this will occur again.

Hwang Jae-ho is a professor of the Division of International Studies at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies. He is also the director of the Institute for Global Strategy and Cooperation. This discussion was assisted by researcher Ko Sung-hwah and Shin Eui-chan.

![[Today’s K-pop] BTS pop-up event to come to Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050734_0.jpg&u=)