[Feature] We saw helicopters firing in Gwangju: US missionary

By Kim Bo-gyungPublished : May 15, 2019 - 16:59

GWANGJU -- Gwangju streets at this time of the year are full of banners on events related to the May 1980 Democratic Uprising as the city remembers the brutal military crackdown on protesting citizens under former President Chun Doo-hwan, with exhibitions, forums, music contests and food sharing.

The deadly military crackdown left an estimated 160 dead and some 5,000 injured in the course of 10 days from May 18, 1980.

Experts say the figure is expected to be higher given that many of the dead were secretly buried and many went missing.

As Chun, who was the defense security commander then, continues to deny accusations of a brutal military suppression and as credible, conclusive facts continue to be elusive, South Korea will commemorate the 39th anniversary of the Democratic Uprising on Saturday with key questions still unanswered.

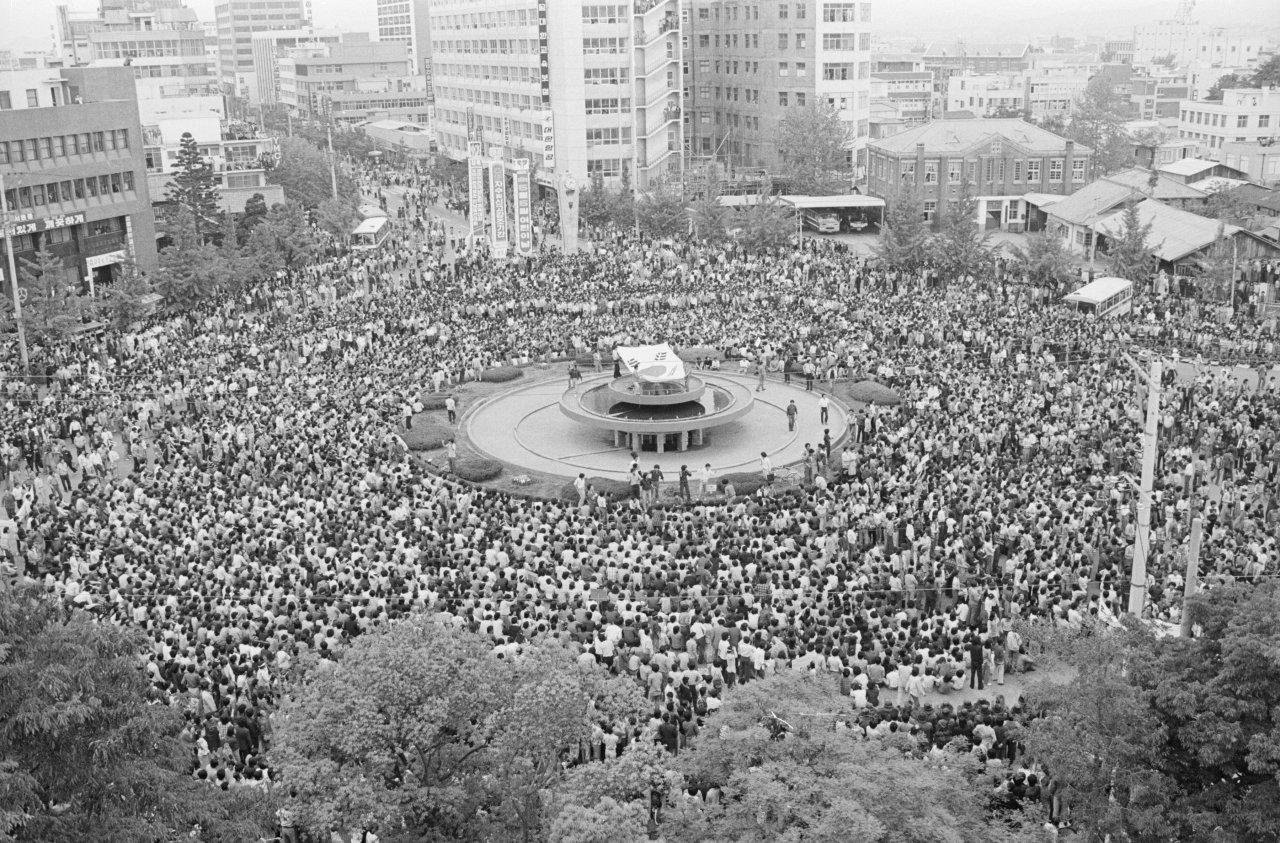

One of the key questions is whether Chun ordered military forces to open fire from helicopters on civilians protesting in front of the former South Jeolla Provincial Government building on May 21. The three-story building was used as a base for Gwangju citizens during the uprising.

The deadly military crackdown left an estimated 160 dead and some 5,000 injured in the course of 10 days from May 18, 1980.

Experts say the figure is expected to be higher given that many of the dead were secretly buried and many went missing.

As Chun, who was the defense security commander then, continues to deny accusations of a brutal military suppression and as credible, conclusive facts continue to be elusive, South Korea will commemorate the 39th anniversary of the Democratic Uprising on Saturday with key questions still unanswered.

One of the key questions is whether Chun ordered military forces to open fire from helicopters on civilians protesting in front of the former South Jeolla Provincial Government building on May 21. The three-story building was used as a base for Gwangju citizens during the uprising.

“The first thing I think about (Gwangju) is the shooting on the crowd in downtown Gwangju from helicopters. I could not believe that an army would shoot and kill its own citizens. It was totally unthinkable to me,” US Baptist missionary Barbara Peterson told The Korea Herald.

Baptist missionaries Barbara Peterson and her husband, late Arnold Peterson, worked in Gwangju from 1975 to 1982. They also worked with pastors who graduated from seminaries in starting new churches in Gwangju and on Jeju Island.

“We heard heavy artillery gunfire and put our two sons (aged 5 and 8) with our ajumeoni in the basement of our house. … My husband and I then ran up to our rooftop deck to see what was happening. We saw the helicopters shooting down at people and could hear screams,” Peterson said.

She added that her husband took pictures of the scene, which were later presented as key evidence in Chun’s trial.

In his memoir published in April 2017, Chun called late activist priest Cho Chul-hyun a “liar” and late Arnold a “satan” for their testimonies on helicopter shootings, unleashing a hailstorm of criticism.

Chun, who seized power in a military coup in December 1979, was elected president in August 1980 after tightening his grip on the country through the May 18-27, 1980 crackdown in Gwangju.

Despite numerous testimonies and evidence -- bullet marks found in the 10-story Jeon Il building located across the street from the provincial government office -- Chun repudiates the helicopter shootings.

“Chun denies that martial law forces shot civilians from helicopters because it is not a form of self-defense, rather a planned massacre of civilians,” Lee Gi-bong, secretary-general of the May 18 Memorial Foundation, told The Korea Herald.

Acknowledging the helicopter shooting would mean admitting to a “systematic crime against humanity,” he added.

Further buttressing allegations that Chun was responsible for the mass shooting, earlier this week, former US military intelligence officer Kim Yong-chang, who was on a mission in Gwangju during the uprising, testified he was informed of Chun’s arrival in Gwangju at noon on May 21, 1980, by a credible informer. It was widely presumed among his informers that Chun ordered the helicopter shootings that began at around 1 p.m. in front of the former provincial government building.

Military forces’ power abuse

The special fact-finding committee on the May Democratic Uprising, whose formation has been delayed for several months, is charged with investigating details of the incident, including: person or persons accountable for the incident; the exact number of people killed, missing and injured; where the military buried the dead; and sexual harassment by the military.

“As I looked down (from the hotel), the soldiers made a group of either middle school or high school students kneel on the ground on the street. The soldiers were going down the line and kicking each student on the buttocks with the heel of their boots. This was so uncalled for because the students had no weapons,” said Peterson.

The Petersons witnessed the scene at a hotel in downtown Gwangju, where they went to check up on four Baptist pastors from Florida after the South Korea-US Crusade initially scheduled to start on May 18, 1980 was canceled.

According to Peterson the event was put off due to strict curfew imposed following the declaration of an emergency martial law nationwide on May 17 and could pose a danger for people attending evening services part of the Christian revival meeting.

“What struck me is the arrogance. There was no concern for the people, it was utter arrogance that they were the ones calling the shots,” Paul Courtright told The Korea Herald, adding that he witnessed soldiers kill a young man at a bus station in Gwangju on May 19,1980.

Courtright treated Hansen’s disease patients in villages near Gwangju in May 1979-September 1980 as a member of the 48th Peace Corps Korea group.

US turns a blind eye

With lawmakers and experts on the uprising increasingly calling on the US to return core evidence of the incident to Korea, questions are rising whether Washington gave the martial law junta the green light to proceed with the crackdown.

“The US’ priority is its own national interest. It was notified of the atrocities in Gwangju by Chun beforehand and condoned it afterward,” said former US military intelligence specialist Kim Yong-chang who now lives in Fiji.

“Due to the lessons it learned in Iran, the Jimmy Carter administration ultimately ended up taking the new martial law junta’s side. For the US, the illegitimate presidency of Chun was more convenient, because it could control him as it wished.”

Kim, who was with the US military’s 501st Military Intelligence Brigade in Gwangju, claims he sent 40 reports to US authorities during the uprising of which three were read by then-US President Carter.

The aloofness of the US government was echoed at its embassy in Seoul, where Courtright visited to inform them of the severity of the situation in Gwangju.

“I sat there (on May 26 around 8 p.m.) for two hours and nobody took my story seriously. … It was really disappointing, because I expected my government to want to know what was going on. … For whatever reason, they did not try to find out,” he said.

What next?

At the heart of the grief and agony of citizens who lived through the bloody crackdown and the bereaved families whose loved ones died in the uprising is the absence of a heartfelt apology.

Chun and former President Roh Tae-woo were sentenced to life in prison and 17 years in prison, respectively, in 1996 but were released in December 1997 in presidential pardons by then-President Kim Young-sam after serving 250 days.

“We forgave them too easily and the punishments were too vague. If we had forgiven after a sincere apology from those responsible for the military crackdown, we would not be dealing with distortion of history today,” Kim Tae-jong, head of research at the Gwangju Metropolitan City 5.18 Archives, told The Korea Herald.

Kim, who was a senior at Chonnam National University, participated in the uprising, writing notes for public announcements and speaking in front of crowds.

“Facts concerning the victims of the uprising have been revealed somewhat. But the truth about the perpetrators at the peak of the crackdown have not yet been revealed. It is an uncomfortable truth of state violence that some may not want to admit to,” Kim added.

“They -- Chun and Roh -- have to kneel before history and citizens. For our society to move forward, we have to address the past, covering up will only exacerbate the situation.”

By Kim Bo-gyung (lisakim425@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)