(3) Passages through Unknown Realities

By C.H. Choi

I. A Return Trip

This May, I will be returning to my hometown of Seoul to serve in the South Korean military. It’s quite a move after studying and working in the U.S. for the past five years, but I’m more daunted by the practical realities of shipping my belongings across the Pacific than the prospect of adjusting myself to a hierarchical, hyper-masculine military culture. Perhaps it is because many of my male friends have already finished their services and were discharged with little trouble. Maybe I have already given enough time to consider how this sudden, three-year separation from civilian life will take shape regarding my relationships, aspirations, and values. But the most compelling reason for my indifference towards military service seems to be the fact of its unavoidability.

Apart from the obvious cultural connotations that it carries for Korean men—as a “rite of passage,” quite naturally so—military service features in the imagination of all South Koreans, as a reminder of the division of the Korean peninsula. This is achieved through deliberate, nuanced mechanisms that govern our political, social, and educational atmospheres. These apparatuses vary in form, ranging from writing mandatory thank-you letters to soldiers as a part of the Armed Forces Day celebrations to witnessing conservative politicians use pejorative terms such as “commies” and “pro-North,” but they inevitably point to the acutely palpable presence of the “other” half of the Korean peninsula.

The presence of this “other” has produced a dichotomous mindset that still pervades in many facets of Korean society. The psychology of the divided nation seems to be intricately related to the exclusive in-groups that have emerged in postwar Korea: Koreans versus non-Koreans, Southeast (Youngnam) versus Southwest (Honam), pro-US conservatives and anti-US liberals. The ideological constructs behind such groupings may seem heavy-handed, but they are telling examples of how the psychology of allies against enemies are at work in our everyday. Unfortunately, the disintegration of society that was brought about by this entrenched, pervasive dichotomy developed over the years is just as real as it was two decades ago, complicated by more recent problems of gentrification, immigration, and economic segregation.

Minouk Lim’s practice is rooted in tracing and empowering marginalized individuals that have been sidelined from the rapid processes of democratization and urbanization in South Korea. As she deftly merges installations, videos, and performances, she brings attention to those who have been categorized as the “other” in modern Korean history, imagining how these silenced narratives can be remembered and commemorated at present. The complexity of experiences in her work, however, allows Lim to do far more than simply shedding light on the disenfranchised. Her projects obfuscate conceptual binaries ingrained in our daily lives and encourage us to reformulate our understanding of everyday reality. At a time when the emotional solidarity of the Korean diaspora is rapidly diminishing, her oeuvre, which activates its spectators through engaging with their participatory potential, is particularly timely.

II. Where Tears Are Shed and Families Are Reunited

The screen juxtaposes two channels that show masses of people grieving uncontrollably. Accompanied by slow, grave tunes of the cello, the camera rolls around public squares where the masses are dressed for funerals and zooms into individual faces. Each of these faces expresses a loss and torment so severe it connotes existential angst. The endless flows of people suggested by the depth of field indicate that these two channels, which are uncannily similar, present a kind of public mourning—the loss of a leader dearly admired by everyone. But the empathy that the viewer experiences in such tormented faces transforms into an eerie sense of discomfort when she learns that the footages of funerals are from a former South Korean president Park Chung Hee (1917-1979) and a longtime North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Il (1942-2011). The explicitly imperceptible contrast between the two broadcast footages clarifies the roles of the objects surrounding the video: a prompter, light boxes, a jimmy jib camera, and a newsroom desk. On top of the news desk, burned and blackened, sits a prompter that directly addresses the viewer with grim statements and questions delivered matter-of-factly:

The camera doesn’t record the ending anyway.

Congratulations on taking it over.

What did people do to remember?

Originally presented at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, Korea (MMCA), The Possibility of the Half (2012) is a reconstructed broadcasting studio where the history and the future of the Korean peninsula are reimagined.

As the rearranged pasts of the two Koreas collide with Lim’s surrealist narrative of reunification in The Possibility of the Half, the artist questions to what extent the media feeds its own version of reality into our understanding of history. The presence of broadcasting equipment renders the installation into the spatial setting behind the creation of televised realities, in which ideological hegemonies are at work to produce artificial dichotomies. Only the select few can participate in the process of creating media, but Lim extends the invitation to the viewers to “occupy” the broadcasting studio with their presence, as she mentions in an interview with the MMCA . In the video and the equipment are traces of fire, which communicate as forms of destruction, but from these debris of obliteration arise opportunities for recuperation and reproduction. It is two megatons of hypothetical tears, produced from compassion and solidarity, that have the power to break down borders—the literal border of the Korean peninsula and the metaphorical boundaries of collective dichotomous psychology. The experience of sympathy and perplexity reiterates the significance of the spectators as sentient, historicized subjectivities—simultaneously complicit and subject to the apparatuses of writing and remembering history.

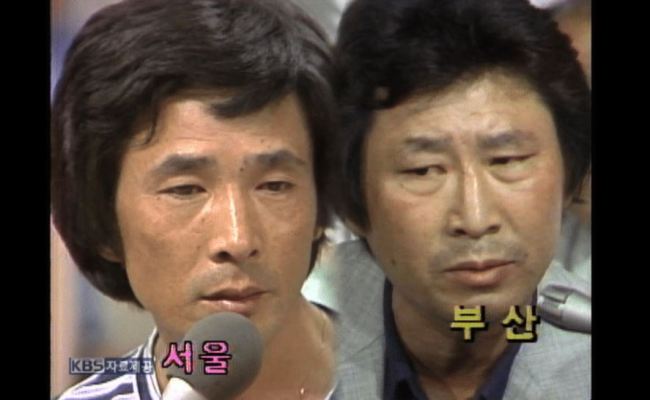

Lim’s interest in revealing the pretenses of mass media is also evident in a more recent project presented at her midcareer retrospective at PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art. With a small strip of space in between, two screens facing each other show edited footages of the live broadcast “Finding Dispersed Families” that was aired in 1983 on Korean Broadcasting System (KBS). The participants, holding signs with hand-written descriptions of their lost relatives, sorrowfully recount the stories of their separations during the Korean War. At certain moments, the screen is split vertically or in multiples, juxtaposing the faces of participants that are cross-checking the facts of their partings. Disappointments arise when the other party doesn’t turn out to be a long-lost family member, but the joy and ecstasy that the participants express when they find their loved ones are explosive. The gravity of these emotions is intensified by the unforeseen moments of immediate physical recognition and hyper-detailed memories despite the few decades that past since the end of the War (“Do you not remember you have a mole on your back?” “Do you recall how you used to sew clothes for me?”). While The Possibility of the Half engaged with the artifice inherent within the broadcasting studio, The Promise of If ponders its possibility as a physical and a psychological space for encountering the past. Even then, however, the broadcasting studio isn’t rendered apolitical; these raw emotions of sheer bliss are shaped and presented according to the media’s varied apparatuses.

III. Performing Flesh and Blood

While The Possibility of the Half and The Promise of If interact with spectators through using the already familiar language of the media, Lim also explores our complicity in this artificial dichotomy in the perpetuation of preposterous injustice. She engages with these narratives by introducing actual victims and survivors as protagonists in her performances, bridging the psychological distance between the viewers and the performers. Her opening performance for the 10th Gwangju Biennale, Navigation ID (2014), most explicitly works with the desire to create artistic dialogues by inserting herself into the communities that have been marginalized in Korean history. For this performance, Lim organized a live-streaming of a long overdue funeral and commemoration of civilian victims that were massacred during the Korean War. Containers that enclosed remains of the bodies that were murdered in the mass killings directed by President Rhee Syngman (1875-1965) were transported from their original locations in Jinju and Gyeongsan to the public square in front of the Biennale Halls. Descendants and relatives of the victims, who arrived with the remains, were blindfolded and greeted by the mothers of victims of the May 18 Democratic Uprising, which took place in the very city in 1980. These extended families of civilian casualties performed a commemorative rite to show respect to the dead, with helicopters hovering over the square to live-stream the performance, to the exhibition venue and on the Internet.

The gravity of the actions within this performance—physical dislocation of the victims’ remains and commemorative rituals that followed—attests to the severity of wrongdoings committed by the Korean government. Not only were the murdered civilians unjustly charged with merely alleged connections to North Korea and political opposition to the Rhee regime, but also the state’s efforts to recognize its wrongdoings and revisit truths have been inefficient and scant. Thus, Lim’s intervention begins from an already seemingly improbable situation, in which the remains of these killings are housed in university laboratories or natural history museums. Instead of distancing herself from these families as an auteure, however, Lim provides the victims’ families an opportunity to bid them proper farewell and the opportunity for the public to witness the funeral; the customary ceremony of the funeral is transformed into a public performance that can be physically and virtually experienced. Navigation ID is an attempt at subverting the logic that perpetrated the injustices by rendering the victims and their families visible. Spectators are invited as participants and witnesses, collectively experiencing the penetrating sense of loss and sorrow from the victims’ undeserved deaths.

Lim’s interest in creating a space for empowerment is also explored through FireCliff 2_Seoul (2011), a site-specific performance that was presented as a part of an interdisciplinary performing arts festival, Festival Bo:m. In the project, Lim introduces Taeryong Kim, a former political prisoner who was arrested and tortured for the Samcheok Family Spy Ring Case in 1979, in which the Korean government prosecuted a number of families for their apparent ties to North Korea. In the first part of this “documentary-theatre” that took place in the National Theater Company of Korea, the audience watches a conversation between Kim and Hyeshin Jeong, a psychiatrist, in which Kim narrates the experiences of torture in a remarkably unemotional tone. At the end of the conversation, the right wall of the theatre opens and reveals another small performance venue in which Kim’s arrest is re-enacted, while the same scene, live-streamed with a thermographic camera, is screened at the front. As the protagonist narrates, reflects, and performs his own experiences, factual details of personal history are re-interpreted at present. The theatre space that the artist provides to Kim to be the narrator of his own experience, fittingly, was used by the police as a garage to transport prisoners in the 1970s. The artist helps Kim subvert the historical connotation of the site and reclaim ownership of his memories; FireCliff 2_Seoul explores the commemorative potential of performance, where narratives specific to its site are refashioned by the personal memories of the performer.

That the artist’s performers have experienced the contested historical events in the past inevitably raises a question of power dynamics: To what extent is Lim appropriating these historical events for her own artistic objectives? As a group of spectators, are we forcing these victims to relive their painful memories, in the impossible attempt at understanding their pain?

Answering these questions requires a closer look into her earlier practices as a part of Pidgin Collective, which demonstrate the artist’s interest in creating a physical and performative infrastructure for communities around her. For instance, Lost? (2004), an installation of two empty containers at a vacant lot near ARKO Art Center, invited museum personnel, the homeless, and the general public to utilize the space as a makeshift office and shelter. A similar collaborative impetus is manifest in The Tenor and Sweet Potatoes (2004), an absurdist, comical performance in which students from Haja Center, an alternative school where Lim worked as an art teacher, set a small bonfire using scraps from construction sites to bake and eat sweet potatoes, while a famous tenor sang arias on the other side of the playground. While these projects are more focused on creating relationships within the local community where she belongs, the performers in her recent projects are motivated by the desire to recapture their own narrative authority. This is realized by transforming everyday rituals, such as a funeral and a psychiatrist session, into performances that engage with the public; it is ordinary gestures of understanding and commemoration that demonstrate the palpable absence of proper remembrance. The artist positions herself “between the audience and the performer, like a correspondent or editor,” while letting the performers play their own selves, from their own memories and in their own bodies.

While the visceral reality of the living bodies performing their own memories can be interpreted as an act of empowerment, it also brings into question the ethics of critique with regard to her projects . Separating the emotional burden from these performances and considering them within the pure realm of theory seems unjust, but it is even more daunting to offer sensible criticism to the form and content of these narratives. These are projects that suggest that as emphatic human beings, we should commiserate with the victims and their unknown sufferings. And chillingly, this persuasion into empathy resembles the dichotomous psychology that has fueled Lim’s practice; the mindset that prompted the erasure of these victims from the political climate resurfaces, pointing to the psychological trap that governs our own realities. Whether we can ever escape it in unclear. Instead, what Lim introduces is “a progress of contradictions” —rather than creating a portrayal of a specific subject, her projects bring forth in the viewers’ minds contradictions that obscure constructed boundaries. In such bewilderment and confusion, we are invited to reflect critically as a community of spectators with a shared experience.

IV. The Politics of Disappearance

As I was writing this essay, I couldn’t help but summon the memory of watching an interview of Lim on YouTube a few years ago, that made a piercing impression. It was a conversation produced on the occasion of her solo exhibition in the Walter Art Center in 2012, where she comments on the newly commissioned sculptures :

I chose light, malleable materials like sponge, which absorbs pretty much everything. And it will probably perish over time. The materiality of sponge made me think more broadly about what I can do for the people that cannot settle down in one place, and how this influences the relationships with the objects surrounding the exhibition space.

Her words struck a chord, because at the time I wanted to be an artist to leave a lasting trace in the world and claim my existence as artworks that can be preserved and experienced. Making something just to have it disfigured and eventually disappear seemed unthinkable, but also pointed to what was absent in my practice: the visceral need to express and create, despite the unknown future of its byproduct.

Returning to my personal entry point to Lim’s oeuvre seems adequate, since her interest in the notion of disappearance and ephemerality was not fully elaborated in this essay. These are recurring concepts that appear throughout the broader arc of her practice, in the form of a slam poet rapping from the back of a truck, moving through the Seoul’s urban redevelopment zones (New Town Ghost, 2005) or as a series of performances organized around the riverbanks of the Han River for a single occasion (S.O.S—Adoptive Dissensus, 2009). Disappeared or disappearing communities, as well as the politics behind their sudden dissolution, are at the backbone of Lim’s oeuvre—witnessing, imagining, and interacting with their realities, we are left to question the ideologies that have pushed away these communities to the fringes of society.

As I prepare for the return trip, I am reminded of the myriad possibilities of disappearance created by the ideologies ingrained in my own nation. The upcoming separation from civilian that I am about to experience, in which I should perform the identity of a confident, assertive military official, is all too common but is undoubtedly one form of disappearance, or erasure, in the divided country. It will be an experience where I must insert myself into the dichotomies that I have attempted to fight back for a long time. But even where grey areas are not allowed, the reverberations and revelations that I have experienced through Minouk Lim’s will persistently resonate. The slight but powerful glimpses into the painful realities, which would otherwise have been left unknown, will continue to instill in myself the strength to challenge what I am told to think.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Harry CH Choi works in the Department of Media and Performance Art at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He graduated from Harvard University with a degree in Visual and Environmental Studies.

Minouk Lim is an artist who lives and works in Seoul. She works across writing, music, video, installation and performance.

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Today’s K-pop] Ateez confirms US tour details](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050700_0.jpg&u=)